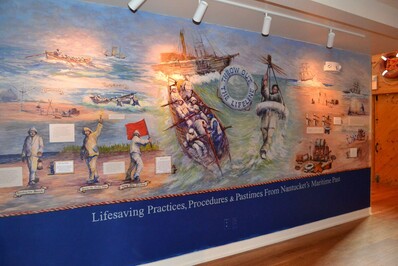

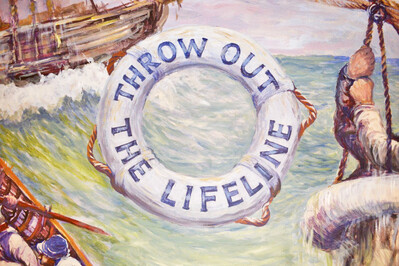

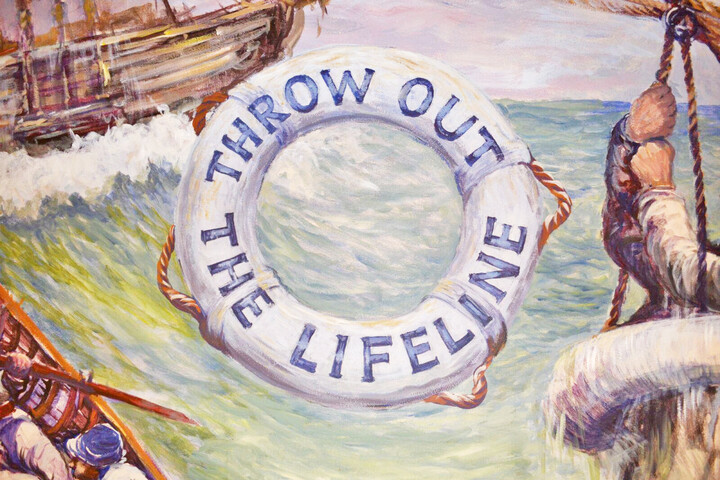

Egan Maritime Institute’s Nantucket Shipwreck & Lifesaving Museum will open Saturday May 24th with a new exhibit “Throw Out the Lifeline”, which honors and explains lifesaving practices, procedures, and pastimes from Nantucket’s maritime past.

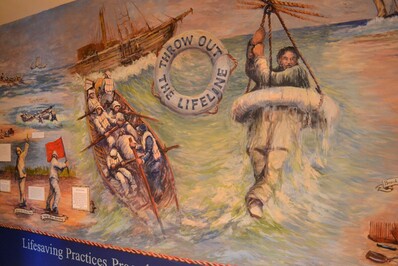

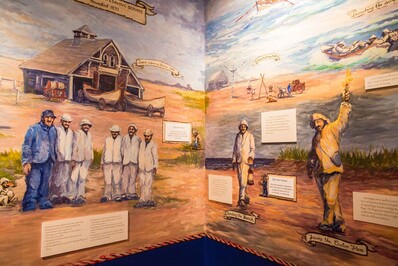

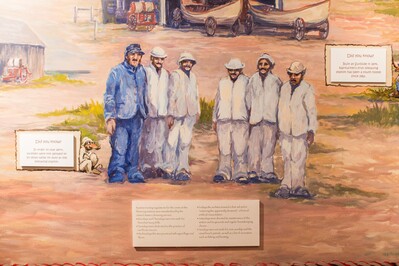

The exhibit visually honors Nantucket’s Maritime Lifesaving history with the display of a four wall mural in the Alison & Bill Monaghan Gallery. This mural was researched, designed, and painted by local artist David Lazarus. The mural tells the chronological narrative of lifesaving practices and procedures, beginning with the conception of the Massachusetts Humane Society and leading up to the present of what is now the United States Coast Guard.

Before the invention of modern transportation methods, hundreds of wooden sailing vessels, coming from across the globe, passed by Nantucket every day. On board they carried everything from sugar, coal, cotton and coffee to more exotic goods such as ginger root, palm oil, pickled limes and rum. Before the ships completed their journey, often headed to New York or Boston, they first had to navigate past dangerous sandbars –Nantucket’s dreaded shoals – and many did not make it. Forging through fog and stormy weather, without the use of GPS or radios, they instead found themselves wrecked in the waters off this tiny island in the Atlantic. People were horrified by the frequent loss of life, and as time passed and the number of lives lost to shipwrecks continued to grow, it was determined something had to be done. And so it begins: The Story of Lifesaving on Nantucket.

In 1785, a group of doctors, scientists and scholars met in a dusky old tavern in Boston to share their ideas – putting together what would soon become The Massachusetts Humane Society, an organization created to address humanitarian issues, including lifesaving. As a result, the first lifesaving huts were constructed around the island and by early 1832, more than a dozen of these shacks were scattered along the Nantucket coast. On Nantucket, these huts were equipped with firewood, a lantern, preserved food, a little bit of furniture, warm blankets and directions on how to signal for help. As the years went by, the MHS worked to improve their program of lifesaving by having lifeboats built and placed along the beaches where shipwrecks were most often sighted. Small houses – early lifesaving stations – were also built to protect the boats.

In 1871, the government stepped in. With national funding that allows paid crews to train together and, therefore, work together more effectively, the United States Lifesaving Service was born. On Nantucket, the first lifesaving station to house a paid crew was built at Surfside Beach in 1874. For the next few years, Captain Joseph Winslow oversaw this elite crew who, on March 9, 1877, responded to their first wreck – that of the W.F. Marshall. As the success of this first station and its crew is fully recognized, additional lifesaving stations were constructed – the next on Muskeget, the small island off the western tip of Nantucket – followed by the Coskata station to the northeast and, lastly, the Madaket station to the west. The crews at each station followed the same daily practices, procedures and pastimes and, in so doing, become a part of Nantucket’s Maritime Lifesaving History. Introduced in the early part of the last century, motorized lifeboats and helicopters have replaced the earlier surfboat and breeches buoy rescue procedures, and have allowed for faster and more efficient rescues farther out at sea.

The Coast Guard, formed in 1915 by the merger of the United States Lifesaving Service and the Revenue Cutter Service, continues the tradition of lifesaving today. Improvements in technology have changed the face of lifesaving today, but the dangers of the sea and the heroism of our professional lifesavers have remained constant throughout time.

To complement the mural, a child-size replica of a Massachusetts Humane Society shack, designed and built by Ben Moore, is in inside the exhibit room. To create an authentic feel of a 19th century humane hut, the shack is illuminated by battery powered candles and contains replica furniture from the era.

On the exterior of the Museum, a rope apparatus is attached to the building, giving children the feel of climbing rigging up to a mast on a ship. Additionally, a new swing set structure is sandwiched between the Museum and Folger’s Marsh; the swings are constructed with life rings and breeches, creating a genuine impression of what it might have been like to be rescued in a breeches buoy.

Photos by Katie Kaizer Photography

With much appreciation and thanks to the following for their valuable time, kind help, creative input and dedication to this exhibit:

- Jeff Allen

- Renee Coleman

- EganSign

- Suzanne Gardner

- Carl Keller

- David Lazarus

- Dick Mack

- Andrew McCandless

- David McCandless

- Tori McCandless

- Ben Moore/Moore Woodworking, Inc.

- Sharlene Rudd

- Glenn Speer