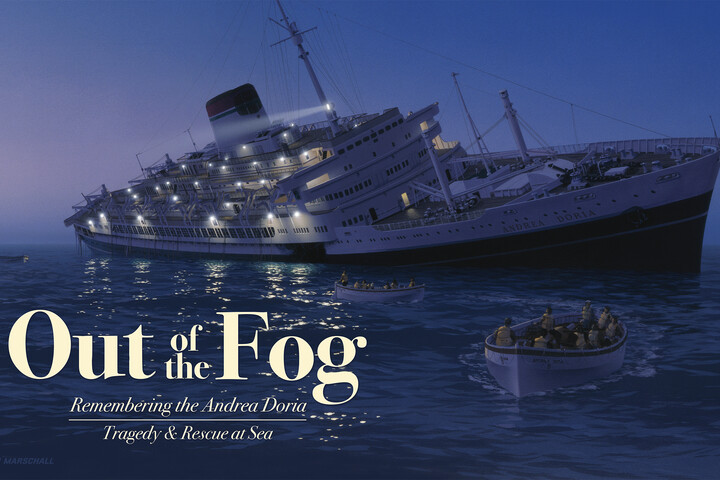

It was a rainy morning in January, 1953 when the Italian Ocean Liner, Andrea Doria made her debut appearance in New York City. The first Italian transatlantic ship launched since WWII, she was considered Italy’s new symbol of national pride. With flags flying, horns and sirens blaring and a fleet of tugs, fireboats, and ferries there to herald her into the harbor, the welcome for this beautiful, state-of-the-art ship was overwhelming.

Sadly, though, just a few years later, in a sequence of badly made decisions, the fate of the Andrea Doria was doomed. On a foggy July evening in 1956 the Andrea Doria

collided with the Swedish Ocean Liner, Stockholm

and sank to the bottom of the sea, 45 miles south of Nantucket. Of the 1,706 people onboard the Andrea Doria, 46 passengers perished along with five crew members from the Stockholm.

On the evening of July 25th the Andrea Doria was approaching America on the last leg of her 101st transatlantic crossing from Genoa to New York City. Prior to docking the following morning, the passengers on board, infused with a mixture of melancholy and excitement, were enjoying a last evening of dinner and dancing as their ship sailed into the fog near the Nantucket Lightship. Captain Calamai was aware of the rules of the sea, stating ships must slow down under poor visibility. However, always under pressure to keep to schedule, he barely slowed, confident his radar would keep him aware of approaching vessels. At the same time, the Stockholm was sailing east under clear skies from New York to Sweden. At 10:00 p.m. the Andrea Doria located the Stockholm on its radar 17 miles distant. At a position 4 degrees to starboard, it was determined the ships would pass each other at a distance of one nautical mile. Wanting to increase that distance, Captain Calamai changed course 4 degrees to port anticipating the two vessels would pass starboard-to-starboard rather then the standard port-to-port rule of passing at sea. Still shrouded in fog, the Andrea Doria had no visual contact with the Stockholm until suddenly the fog momentarily lifted to reveal the Stockholm’s port lights straight ahead. With the sudden revelation the two ships were not passing as anticipated, Captain Calamai ordered hard to port as the Stockholm turned 20 degrees to starboard. These last minute course changes by both ships resulted in disaster.

At 11:10 p.m. the Stockholm rammed into the Andrea Doria. The stricken ship abruptly and dramatically lurched over to port and then righted. Passengers and crew heard the sounds of a grinding crash, and some saw the lights of the Stockholm through the Doria’s windows and portholes. The Swedish ship’s reinforced bow was like a dagger piercing the large Italian liner. She cut forty feet into the Doria’s hull, just below the bridge, creating a jagged hole like an inverted pyramid. It was a mortal wound. The two liners were entangled for a short time until movement tore them apart. Fifty-five feet of the Stockholm’s foredeck and bow were folded into a tangled mass of steel. The Andrea Doria sent out an immediate SOS and soon after began the starboard list from which she would never recover.

Eleven Coast Guard vessels were immediately dispatched to sea following the first calls for help from the stricken Doria, including the USCGC Hornbeam. The Navy transport Pvt. William H. Thomas, the Navy destroyer USS Edward H. Allen, the tanker Robert E. Hopkins and the freighter Cape Ann were also called to the scene. Looming largest out of the night was the majestic liner the Ile de France. En route from New York to France, she was 44 miles east of the Doria when notified of her collision. Skeptical at first that a modern ship like the Andrea Doria could be foundering, reports from other vessels confirmed the severity of the situation, thus prompting the Ile de France to immediately turn around and set a direct course for the stricken ship.

It was soon realized that the badly damaged Stockholm was in no danger of sinking, and so she began to assist the doomed Doria. Below decks on the Italian ship, crewmen struggled quickly and furiously to pump out the floods of invading Atlantic water. Deck crews worked promptly to rig rope ladders and nets so passengers could clamber down the ships sides and reach waiting lifeboats. All the port-side lifeboats were useless because of the severe list to starboard. The Doria’s electrical system fortunately continued to work, along with the huge boat deck emergency searchlights.

Passengers slid down ropes – off stern, off the bow, off the quarter. Small children and the elderly were carried. The steady relay of lifeboats continued throughout the night. The Doria’s whistle moaned continuously – her death rattle. By daylight, the Doria was keeled over and all but abandoned with the last of the passengers removed by 5:00 a.m. At 5:30 a.m., the final lifeboat left the Andrea Doria for the USCGC Hornbeam. On board, Superior Captain Calamai, Staff Captain Magagnini and other crew members were eventually transferred to the USS Edward H. Allen and taken to New York. Had Captain Calamai’s accompanying crew members not threatened to stay on the Andrea Doria with him, if he did not leave, Captain Calamai would have gone down with his ship.

With much appreciation, we give thanks to the following for donating their time, artifacts, and personal stories to make this exhibition possible:

- Karen T. Butler

- Susan Yerkes Cary

- EganSign

- CDR Maurice E. Gibbs USN Ret.

- Linda Morgan Hardberger

- Rick Johnston

- Dick Mack

- Ken Marschall

- William H. Miller, Jr.

- Bambi Gifford Mleczko

- Nantucket Historical Association

- Laura and Ralph Scarola

- Glenn Speer