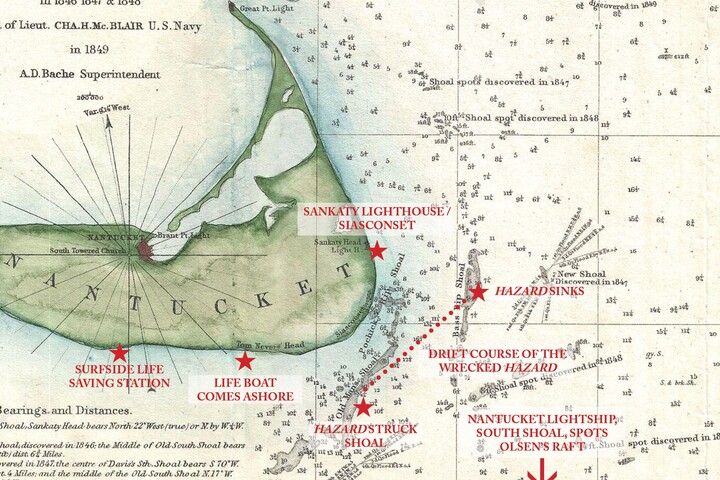

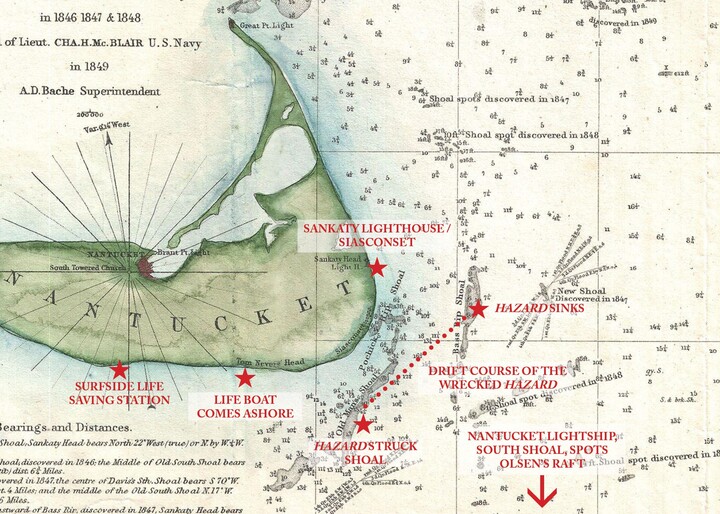

The Mysterious Shipwreck of the "Hazard" off Nantucket's South Shore in 1881

By Olivia E. Jackson and Michelle Cartwright Soverino

The bark Hazard was known for her speed. She was built in Boston, MA in 1849 for the East Indian trade, and had an excellent sailing record during her thirty years of service.

In 1880, under the command of Captain David Roberts, she sailed across the Atlantic to Sierra Leone, on the west coast of Africa, where she was loaded with a precious cargo of hides valued at $35,000. The bark was destined for New York and Boston, but after the long journey, she anchored in Delaware Breakwater for several days. During this respite, Captain Roberts sold the “unseaworthy” life boat, and didn’t replace it before continuing the trip. Allegedly, no one knows exactly why he sold the life boat or why he didn’t immediately replace it. The bark was left with one 14-foot life boat on board, which could only fit four of the eleven crew.

Freetown, Sierra Leone, in 1803. Click here for source.

On February 12, 1881, with a heavy breeze and strong tides, Captain Roberts and his crew set sail for Boston. With favorable winds and a powerful ocean tide, the speedy bark sailed at a quick pace and moved up the coast faster than anticipated. A light on the horizon was spotted on the night of February 13, which Captain Roberts believed to be Montauk; however, it was actually Sankaty Lighthouse on the east coast of Nantucket. The Hazard was far off course.

As the bark approached the dangerous shoals southeast of the island, the wind increased to a gale, forcing the Hazard to drift drastically from its course. In the early morning hours of February 14, the Hazard struck a shoal. However, the bark was able to lift off and continue sailing, but not without significant damage to the vessel. The rudder was smashed in the collision and caused the bark to drift aimlessly in the wind. At daybreak, the bark struck the Old Man shoal, southeast of Siasconset, which completely dislodged her rudder and the ship began to flood. The Hazard was shipwrecked.

The beacon of Sankaty gave hope that the crew would be seen from shore at daybreak; however, the morning light revealed they were far from shore. With only the small life boat on board, the second mate, a young Norwegian man named Emil Olsen, began building a raft with the assistance of two other crew members. Although rudimentary in its construction and design, the floatability of the raft far outweighed other concerns, especially since the bark was sinking.

"Save Sankaty," by Robert Perrin, 1985.

Shortly after dawn, as they began to drift towards the treacherous Bass Rip, Captain Roberts, his first mate, W.H. Chase, along with two other crew members prepared to go to shore to seek assistance. Before boarding the life boat, he gave no orders to his anxious, impotent crew. The helpless, abandoned crew watched their Captain and fellow crew row away. At 9 o’clock in the morning, after an hour of rowing toward shore, Captain Roberts and his life boat crew watched as the ocean enveloped the Hazard, stern first.

At the first sign that that hull was breaking, Olsen, the Norwegian who built the makeshift life boat, and his two helpers pushed the raft into the sea. Olsen quickly jumped aboard, followed by a sailor named Sheridan. Two crew members made a desperate leap, but the raft drifted far enough away from the boat that their attempt was unsuccessful. Thomas Brown, an English sailor, was one of the crew members that landed in the icy water. Luckily, he was hauled to the raft. Four men were still on the bark when it made its final descent. Two were seen struggling to swim and stay afloat after the boat went under. The other two were never seen after they were tossed into the ocean. All four perished in the freezing cold water the morning of February 14, 1881.

Shortly before the Hazard disappeared in the ocean, men on the shores of Nantucket spotted the vessel on the Old Man shoal. They saw no signs of life and no distress signals, and thus assumed the bark had been abandoned. The volunteer lifesavers in Siasconset would have normally launched the Humane Society’s surf boat, but because there was no sign of life and the winds were extremely high, they didn’t risk venturing out for what appeared to be a deserted wrecked ship. They did, however, witness the Hazard drift from Old Man shoal, to the south of Siasconset, to Bass Rip shoal, which was to the east. Olsen and the men on the raft were never spotted from shore as the white water foaming around the rip obscured the onlooker’s vision.

1849 U.S. Coast Survey Map of Nantucket and her surrounding shoals, annotated.

At around 5 o’clock that evening, the Captain’s boat with the three crew members was spotted trying to make it to shore. Having difficulty maneuvering and steering the boat, landing at Tom Nevers Head was difficult. Captain Winslow of the Surfside Life Saving Station and several members of his crew arrived on the beach to help assist the exhausted men ashore. Captain Winslow invited Captain Roberts to go back to the station, but, strangely, Roberts insisted to be taken to Nantucket Town, and an eyewitness spotted him carrying two bags of what appeared to be gold from the life boat.

After having dinner in town, Captain Roberts dispelled a version of the story about the wreck, although the exact details that he released are unknown, and at the time he didn’t even know the fate of the seven crew he had abandoned on the Hazard nor about Olsen’s makeshift raft. Allegedly, he shared little information other than the facts that led to the wreck. Islanders, hearing the story and worried about the crew, responded by sending the steamer Island Home out on the morning of the 15th to search for them. On the shoals, the steamer discovered the Hazard sunk in 10 fathoms (60 feet) of water off Bass Rip and no sign of a raft. After perusing the area and the dreaded shoals, the steamer returned to the wharf with its newfound information. All hope that the seven crew members were alive was lost.

The Surfside Life Saving Station, built in 1874.

There are several strange facts surrounding the wreck of the Hazard. Other than the oddity that Captain Roberts shared little information about what happened and the potential loss of his crew, he wanted to be taken to town immediately. Additionally, he had managed to bring two bags of gold aboard the life boat, but didn’t give commanding orders to his helpless crew before abandoning them. The two crew members that made it to shore couldn’t fathom why Captain Roberts had sold the long boat and why he didn’t replace it before they continued on their journey. They believed that if he had purchased another boat, all of the bark’s crew would have survived.

Despite these curious occurrences, the most miraculous event had yet to occur. After nearly a month since the bark had wrecked and sunk into the ocean, on March 8, 1881, the Nantucket Lightship’s tender, Verbena, arrived at the wharf with two unexpected passengers, Olsen and Sheridan from the crew of the Hazard.

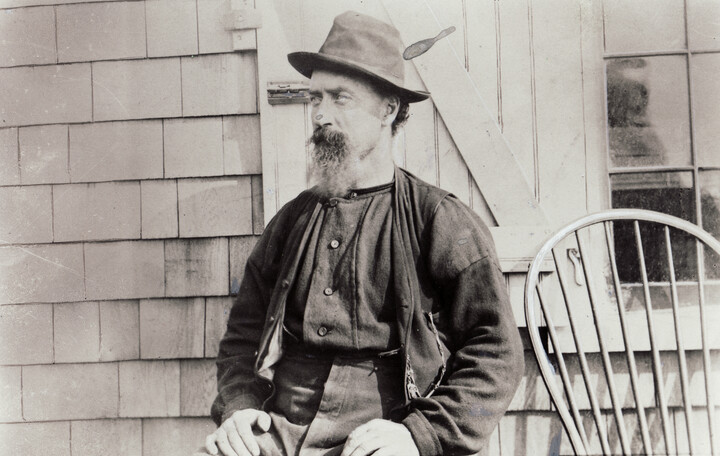

Captain Thomas James and his lightship crew had spotted the raft at 4 o’clock in the afternoon on February 15. A boat, commanded by Mate Sandsbury, who would later become the first keeper of the Muskeget Life Saving Station, was sent to the raft to rescue the men. Olsen and Sheridan were in a precarious position– the raft was beginning to fall apart and the surviving crew was fighting to stay above the surface. At approximately 5:30pm, Olsen and Sheridan were aboard the Nantucket Lightship; the frozen body of Brown was consigned to the sea.

Captain Sandsbury, first keeper of the Muskeget Life Saving Station, and former Mate of the Nantucket Lightship.

Once brought aboard, Olsen shared his story. Diplomatically disclosing details of the wreck, he shared how Captain Roberts left the bark for shore, and the desperate building and boarding of the raft. Olsen didn’t blame anyone for the incident. He described how he and Sheridan tried to keep Brown alive after his immersion in the icy water and that his body was frozen to the point where he had to be tied to the raft in order to prevent him from sliding off. Olsen recounted that only one man at a time could sit down on the raft, otherwise it would sink. He mentioned how the two men spotted different vessels nearing them, including the steamer Island Home, giving them feelings of hope, only to be crushed when the boats turned around.

On March 8, 1881, the arrival of Olsen and Sheridan on Nantucket confounded the mystery and strangeness associated with this wreck. According to an Inquirer and Mirror article published in January of 1941, “the second mate said that when it became apparent the Hazard was doomed he suggested to Captain Roberts that the bark be run ashore so all hands might have a chance for their lives. When the Captain refused this suggestion Mate Olsen began to build his raft.” Days after the wreck, questions about the Captain’s actions were numerous. Why did the Captain sell the long boat? Why was he not aware of his surroundings? Why did he bring gold ashore? Why did he want to be rushed to town? What details did he share about the wreck and why was his story different than the other survivors’ accounts? Although hypotheses and speculations have been made, the true answers are, and always will be, a mystery.

Authors' Note

Recounting the sequence of events that lead to the dismal end of the Hazard was no easy task. No two sources shared the same details, and much like the wreck, mystery remains. It would be fascinating to know what happened to Captain Roberts and the three crew who made it safely to shore with him. What happened to Olsen and Sheridan after arriving on the island in March of 1881? What about the gold? There are so many unanswered questions, and the truth will never be known. But what is clear, is that seven men were left to perish in the cold waters off Nantucket, and had better decisions been made, perhaps they all would have lived.