It Will Be a Long Time Before the Day’s Deeds Will Be Forgotten

By Michelle Cartwright Soverino

The two-masted schooner Eveline Treat was sailing along the south shore of Nantucket, heading to Gloucester, MA, with a cargo of coal during the early morning—around 1am—of Saturday, October 21, 1865, when she struck Miacomet Rip. There were five souls aboard the ship: sixty-two year old Captain Job Philbrook, two of his sons, and two other men. Under the cloak of darkness they had no option but to weather the waves with hope that the Eveline Treat would survive the night and that they would be spotted after day break and rescued.

“The vessel was heavily laden with coal; the sea carried away her house on deck, soon after, and as her helm had become crippled and unmanageable, she was at the mercy of the elements. For many long, weary hours these unfortunate men had been exposed to imminent danger. The wind had blown fiercely through the night, and the waves swept her decks continually.” (Inquirer & Mirror, "Marine Disaster.” October 28, 1865.)

The wrecked schooner was sighted the following morning, fast on Miacomet Rip, from the island's Old South Tower. The Humane Society’s Surfside crew responded bringing their lifeboats to the beach, where they realized the high surf and wind would delay any launching. The Eveline Treat was roughly 300 feet off shore, and Captain Philbrook and his men had lashed themselves to the rigging. The waves continued to break over the vessel. The Humane Society employed their mortar apparatus on the beach to secure a line to the schooner. One of Captain Philbrook’s sons climbed down from the rigging to collect the line and then carried it up to the shrouds of the foremast, and pulled the hawser out to the vessel from the shore to secure the line between the schooner and the beach.

Miacomet Rip, photo by Van Lieu Photography.

“A sling was then hauled to the wreck, this then being the conveyance to bring men ashore; the modern breeches-buoy not yet designed. Captain Philbrook’s sons tried to persuade him to go first but he refused and the mate took his place. Nearing the beach the line snarled.” (Life Saving Nantucket, Edouard A. Stackpole.1972, Stern-Majestic Press, Inc.) As he dangled in the sling above the ocean, it was impossible to verbally communicate with the Humane Society men onshore as the roaring waves were far louder than the reach of the mate’s exhausted voice. “A line was thrown to the man in the sling, who caught it, and immediately fastened it about his waist, and leaped into the sea. By the joint efforts of those on the shore, the man was rescued, and borne safely to the land, and quickly to town, where we was warmed and refreshed by willing hands. The second man, one of the Captain’s sons, was brought ashore in a similar manner.” (Inquirer & Mirror, "Marine Disaster.” October 28, 1865.)

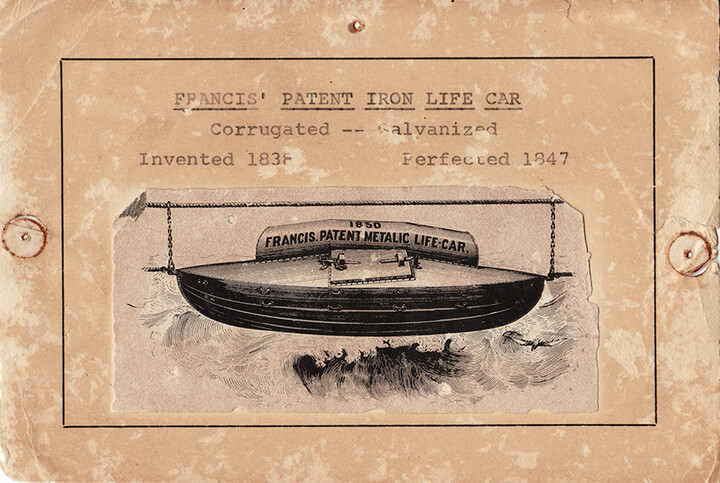

Three men were still aboard the wrecked Eveline Treat, and though his remaining son and seaman implored him to get into the sling and make his way to shore, Captain Philbrook refused. On shore, Daniel W. Folger volunteered to head out to the schooner to rescue the Captain. The Humane Society crew attempted to use a metal Life Car and adjusted it to the hawser to take him to the ship, but the car was unable to make it out to the vessel. The sling and its seat were the only working options for the retrieval of Captain Philbrook and his two remaining crew, who had now been lashed in the rigging for many hours, and were exhausted, soaked, and without food and water. The scene was becoming increasingly desperate.

“Finally the young sailors on board were successful in helping the old man to his place in the seat, and when they had firmly bound him, managing hands on shore pulled with a will, each one earnest to succor him whose age and cheerless situation awakened the deepest sympathy in the hearts of all. Slowly he was drawn landward. For one so apparently helpless, the tenderest regard was manifested. When mid-way between the vessel and the beach, the line became entangled in the hands of the men in the rigging, and for an hour and a half, perhaps, the Captain hung, swinging over yawning surge, wet and cold. The men in the shrouds, still worked upon the snarled rope, with a Trojan’s will; but it would not give away.” (Inquirer & Mirror, "Marine Disaster.” October 28, 1865.)

The life car, which was unable to make it out to the Eveline Treat to rescue Captain Philbrook and his remaining crew. Nantucket Shipwreck & Lifesaving Museum collection.

The evening was approaching night and the Humane Society crew knew Captain Philbrook and his men could not last much longer. A young Nantucket man, Frederick W. Ramsdell, recognized the perilous state and dismal fate on the horizon for Captain Philbrook, and took action. “After fastening a line around his waist, [he] caught hold of the hawser and began a precarious journey along it, hand over hand, with his feet twisted around the heavy rope so as to maintain an upside-down posture. Slowly, he crawled along the hawser, over the breaking seas, until he reached the sling, all the while holding in his teeth an open knife. With one hand he cut the line connecting the sling to the schooner, then quickly made the line he carried fast to the sling.” (Life Saving Nantucket, Edouard A. Stackpole.1972, Stern-Majestic Press, Inc.)

The Humane Society men on the beach then hauled away, working quickly to bring Captain Philbrook and Ramsdell to shore. The lead line from the schooner was then attached back to the sling, and the two remaining men aboard the Eveline Treat were brought to safety on shore. The islanders who had gathered on the beach and had been watching the rescue throughout the day and evening, returned home knowing no life was lost thanks to the unwavering people of Nantucket. “It was not a great while before the last two men were landed, and our citizens with light hearts, wended their devious ways homeward. Darkness crept on space; but the lights around every fireside burned brighter that night, and eyes opened wider, at the thrilling story of five men who were rescued from a watery grave. God was thanked, and the brave man was remembered, who risked his own life that three men might live. It will be a long time before the day’s deeds will be forgotten—the memorable 21st of October, 1865!” (Inquirer & Mirror, "Marine Disaster.” October 28, 1865.)

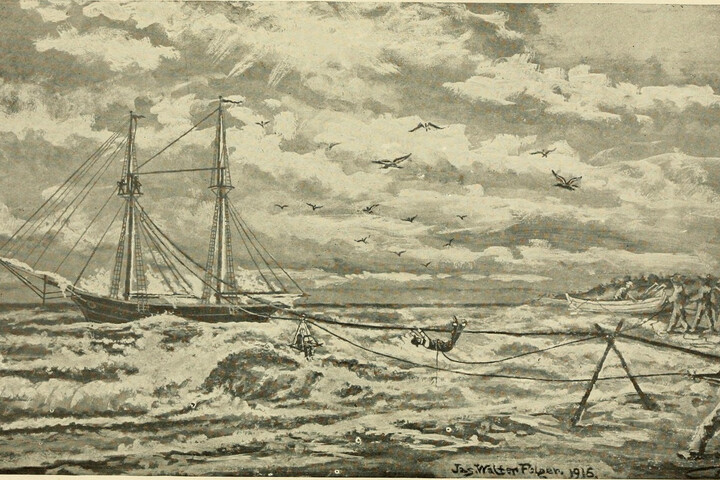

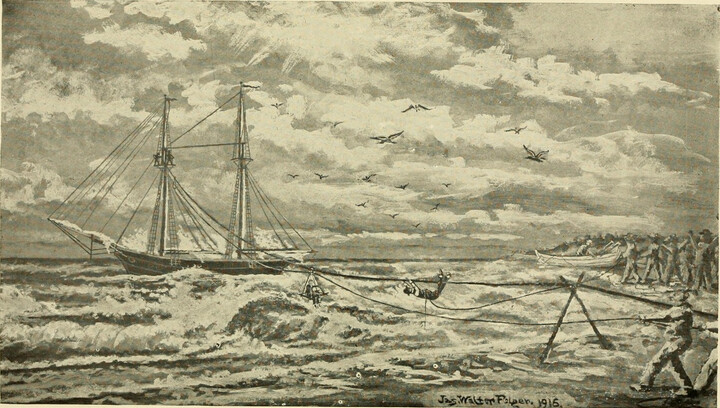

Depicted, Frederick W. Ramsdell makes his way to Captain Philbrook who is stuck on the line halfway between his ship and the shore. "Schooner Eveline Treat, Wrecked at Miacomet Rip, Nantucket," by James Walter Folger, (b.1851 - d.1918). WikiMedia.

The vessel and cargo were a total loss. Two weeks after the rescue, in the November 11, 1865 issue of the Inquirer & Mirror, it was announced that Ramsdell was to be awarded a silver medal from the Humane Society for his “gallant conduct in rescuing the Captain of the schooner Eveline Treat, wrecked at the south side of the island on the 21st. This is the highest award now given by the Society for meritorious conduct in saving life.” In a letter printed in Captain Philbrook’s home town newspaper of Bangor, Maine, he wrote,

“Feeling that some expression of gratitude is due to the kind people of Nantucket for their timely aid and generous hospitality, tendered to myself and crew, when taken from the wreck of the ill-fated Eveline Treat, I take this opportunity of expressing my sincere gratitude through your columns.

Having been thirty-six hours upon the wreck without food and also without clothes—fifteen of which were spent in the rigging—when all hope of rescue was fast expiring and a miserable death seemed inevitable, help came through the efficient services of the ‘Humane Society,’ conducted by Alexander B. Dunham, Joseph Hamblin, and associates—help which no other means could have rendered, and when after hours of weary watching, we were at last on shore, then did we feel the hospitality of the people. Carriages were in waiting to convey us to homes of comfort and with the greatest dispatch all our wants were met. In our pitiable condition we were prepared to appreciate such unselfish kindness.

To the brave Frederick Ramsdell, who nobly offered to ‘shin’ along the line and cut the small one leading from the vessel, should we render our thanks.

Mrs. Philbrook wishes to share in expression of gratitude, and hopes a merciful Providence will deal gently with a people who saved her husband and two sons from a watery grave. The mothers of the other two add a ‘God bless you,’ and their earnest thanks. One and all, we would say, ‘go in your deeds of kindness, and when Our Father makes up his jewels, He will say unto each, Well done good and faithful servant; enter thou into the joy of thy Lord.’” Job Philbrook, November 23, 1865.

On the 10th anniversary of the wreck and the rescue, the Inquirer & Mirror, in its Saturday Morning edition on October 23, 1875, remembered the events that unfolded on the island’s south shore, “The hundreds of our people who gathered on the bleak shore, near Miacomet, ten years ago—the 21st of October, 1865—will recollect now the heroic act of Mr. Frederick W. Ramsdell, formerly of this town, in rescuing the captain and a number of the crew of the Eveline Treat, a coal vessel bound from Philadelphia to Gloucester.”

Over 150 years later, we still remember the day’s deeds and the heroic efforts of Frederick W. Ramsdell, who is forever part of Nantucket’s unwavering human spirit and lifesaving legacy.