From Humble Beginnings

By Nathaniel Philbrick; Portraits by Cary Hazlegrove

Nantucket Magazine, Midsummer 1996

Trying to find Albert “Bud” Egan, president of the rambling collection of showrooms known as the Marine Home Center, is an adventure in itself. By the time you weave your way through the home-furnishings department, take a left at floor coverings, and climb two flights of stairs, you begin to feel a little bit like Dorothy in search of the Wizard.

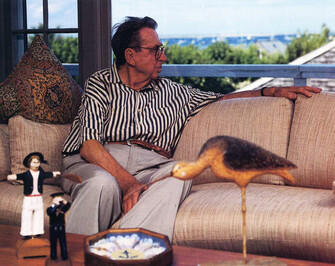

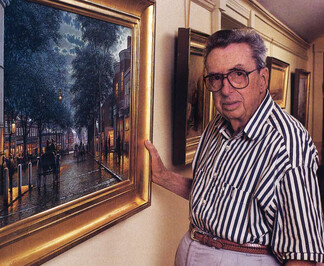

Considering that it sits atop a lumber yard, Egan’s office is a marvel: a spacious room full of artwork, ship models, and sculptures with a breathtaking view of Nantucket Harbor. And there, sitting behind a large desk stacked with books, magazines, and a sign that reads “God so loved the world that he didn’t send a committee,” is the man himself talking on the phone.

Although approaching his eightieth birthday, Egan shows no signs of slowing down. Every day he methodically works his way through the company’s mail—no small feat considering that Marine Home Center employs more than a hundred people, making it Nantucket’s largest private employer. While he also manages to fit in a few holes of golf every morning at his beloved Sankaty Head Golf Club, it is a rare day that he leaves the office before seven o'clock at night.

On this particular afternoon, Egan motions for me to sit down before handing me a calendar from a local insurance company that features a now famous photograph: the Nantucket steamship stuck in the ice a couple hundred yards from the island’s shoreline. The passengers are off-loading across the ice, and in the foreground is a young couple, the father carrying a baby bundled up against the cold.

Egan puts down the phone. “See the baby?” he asks. I nod. “That’s me,” he says, “in 1918.”

The Bud Egan story begins around the turn of the century in Leominster, Massachusetts, when his father—also named Albert—lost both his parents. The authorities dispersed the children among several orphanages, but it wasn’t long before Egan’s father, then all of twelve years old, had run away and joined his older sister Bertha in Lynn. Eventually Bertha and Egan’s father were joined by two more of their brothers, Harry and Bill. Bill’s experience as a railroad engineer during the construction of the Panama Canal won him a job offer from—of all places—Nantucket Island, where there was a small-gauge railroad that took summer people from Steamboat Wharf all the way out to ‘Sconset.

A Nantucket directory published in 1914 lists the four of them as living in the cottage None Too Big in ‘Sconset. Although Bertha, Harry, and Bill would eventually leave the island, Egan’s father stayed on, first working for Oscar Folger in the livery business, then learning the carpentry trade. By 1915 he had married a local ‘Sconset girl named Frances Coffin. Albert, Jr., the first of four sons, was born in 1916.

It wasn’t long before Egan’s father began to establish himself as a builder, ultimately constructing more than twenty-five houses in ‘Sconset, including the cottages that are today part of the Summer House Complex. Of his father, Egan says, “Although he had no formal education to speak of, he had a keen sense of form and design. The houses he built were very much in keeping with what was already there.”

But making a go of it on Nantucket in the 1920s, and especially the 1930s, was very much a relative thing. Says Egan, “Money was unheard of in those days. My mother’s family may have had sterling silver and linen tablecloths, but I can still remember the holes in those tablecloths. They were proud as proud as proud can be, but they had no money.”

Even though times were hard, Egan remembers when his Great Uncle Eddie Coffin decided to retire at the age of fifty—a fairly common practice in those days. When a well-to-do summer person for whom Eddie had been a caretaker asked how he was to afford his early retirement, Egan’s uncle replied, “It’s not how much you make, it’s how little you spend.”

“I never knew anything but work,” Egan says of his childhood. Whether it was assisting his mother at the ‘Sconset Bookstore in the summer, caddying at the golf course, working at John Salvas’s Gas Station (where you could also get a haircut), carrying special deliveries for ‘Sconset postmaster Phil Morris, or shucking scallops by lamplight after school, Egan quickly gained experience working a wide variety of jobs.

In those days ‘Sconset was its own year-round world, independent of “town” to the west. It had its own elementary school, where twenty or so students were taught by a single teacher. In July and August it had its own group of summer people—many of them actors, artists, and writers—and throughout the rest of the year ‘Sconseters had other ways of getting by, one of which was codfishing. Egan can still remember the dories, filled to the gunwales with fish, surfing in on the seventh wave (“always the biggest”), and the huge, open casks of salt cod covered by “green flies an inch thick.”

Yet another fact of life in ‘Sconset during the era of Prohibition was rum-running. Since it was an out-of-the-way village on an already remote island, ‘Sconset was the perfect place for bootleggers to stockpile their wares. “All of a sudden a new padlock would appear on the door of an old fishing shack,” Egan remembers. “We all knew what was going on.”

Although his father forbade him to have a gun, Egan, who become a devoted fan of the Zane Grey series of westerns, saved the $2.50 required to order a single-shot .22 rifle from Sears, Roebuck. Taking his cue from the rum-runners, he kept his gun well hidden in a fish shanty, and after school he and his pals would wander the beaches and marshes shooting ducks. But it wasn’t just waterfowl. The empty hotels with all their glittering windows, Egan now admits, were also “very inviting for a boy with a gun.”

In the fifth grade, Egan and his classmates started attending the Academy Hill School, traveling back and forth across the moors on an open-air bus used for tourist excursions in the summer. Although he temporarily returned to ‘Sconset for sixth grade while the brick structure that presently stands atop Academy Hill was being built, it became clear that going to school in town was not without its advantages. For one thing, it was now possible to fish from the town wharves during the lunch break.

School wasn’t the only thing that brought Egan to town. There was also the movies at the present-day Dreamland Theater where in the days of silent film Billy Blair provided the musical accompaniment. “Just prior to a show, he would walk down the aisle to great applause,” says Egan.

Being a ‘Sconseter meant that Egan had to get himself home if he missed the school bus, making it difficult to participate in sports. This wasn’t enough, however, to keep him from playing outfield on the high school’s baseball team. “Afterwards I’d do my best to bum a ride,” says Egan, “but there wasn’t much traffic in those days. There were telephone poles along the Milestone Road, and I used to run two, walk one, then run two again. Sometimes I’d do that all the way home without seeing a car.”

Considering that ‘Sconset was home to one of the world’s first and most famous wireless stations, it was not surprising that Egan became “enthralled with radio” at a very young age. By fourteen he was fixing and selling old radios, and by the time he graduated from high school in 1935 he’d signed up for a one-year “radio school” in Boston. Then it was on to the RCA Institute in New York City.

But Egan quit what was to be a two-year course after only a year. “I could have been a telegraphic operator on a ship, but I decided it wasn’t for me.” Several years of being “sort of lost” followed, with Egan spending his winters as the night manager of a gas station in Hollywood, Florida, but devoting most of the year on-island working for his father in the construction business.

During this period Egan met a young woman from Nova Scotia named Dorothy Harrison who had recently arrived on island to work as a dietitian at Nantucket Cottage Hospital. Even though Dorothy had been warned by the head of nursing “not to get involved with any local boys because you’ll end up supporting them for the rest of your life,” she and Egan quickly fell in love. They were married in 1940.

In those days only one boat ran each day to Woods Hole, and it was customary for a couple to be married early enough to make their way on the steamship at 6:30 in the morning. So, after a quick wedding ceremony at daybreak, the newlyweds were off to Nova Scotia to visit Dorothy’s parents.

Although we tend to think of the seasonal “housing crunch” as a fairly recent phenomenon, it was, if anything, even worse in the 1940s. Bud and Dorothy were able to rent houses on Main and Fair streets during the first two winters of their marriage, but were unable to find a place where the two of them could afford to live in the summer. This forced Dorothy to return temporarily to hospital housing, while Bud lived with his parents in ‘Sconset. It was then that Egan’s previously directionless professional life gained a clear and immediate focus: he would build them a house of their own.

After scraping together the money required to buy a lot on Quaker Road and then purchasing a derelict three story house on the North Bluff in ‘Sconset from the bank for $100, Egan set out to make his dream a reality. While Dorothy worked at the hospital, Egan spent an entire winter working twelve to fourteen hours a day—tearing down the house in ‘Sconset, taking all the nails out of the lumber, cleaning up all the brick, and selling what he couldn’t use. After working for his father that summer, he went back at it—digging the cellar by hand, pouring the foundation, and then building the house almost entirely by himself. A $2,000 loan ran out before Egan was able to finish the kitchen, so he and Dorothy made do with curtain-covered egg crates for cabinets.

When the war broke out in 1942, third-degree flat feet made Egan ineligible for active duty. After a stint building barracks at Ft. Devens, he was back on Nantucket as a member of the Coast Guard Auxiliary. He was also, once again, working for his father. “I was in a kitchen working with Elmer Watts and I said, ‘This is not for me, I’m going into business for myself.’ An hour later I told my father and that was it.”

Egan started his own construction business, the Island Building Company. “I had a concept. I gave the customer a price, and win, lose, or draw, I’d stick with it. I also did some caretaking. Every two weeks I’d send a client a penny postcard with an update on his property, and people seemed to like it.”

At this time, Nantucket was still stuck in the economic doldrums. “In those days,” Egan explains, “the average salary on the island was ten percent less than on the Cape, even though things cost ten percent more.” He also points out that the summer people had no incentive to see any of this change. “They liked the fact that Nantucket was a sleepy little town, since they didn’t have to pay people anything to work for them. But for those of us who lived year-round on the island, it was tough.”

In 1944, Egan was approached by Lawrence Miller, a businessman from New York with homes in ‘Sconset and on the Cliff who had recently bought a lumberyard on the island. Egan credits Miller with being one of the first people to try to pump some life into the island’s economy. “He could see that Nantucket needed a boost. But for the next ten or so years, he seemed to be working at it all alone.”

Even though Egan was only twenty-seven years old, he had come highly recommended by Harrison Gorman, an older friend who worked for the island’s gas and light company, and Miller offered him the job of running the lumberyard. So, with no experience in the business that would prove to be his life’s calling, Egan opened the doors of the Marine Lumber Company in 1944. A year later, the Egans had a daughter Jane.

From the beginning, Egan says, “I was ambitious as hell.” With Herb Sandsbury and Roy Ryder holding down the fort at the lumberyard, Egan began to expand the company’s operations to include an ever-evolving group of specialties. “Back then the summer lasted only sixty days, then you had the other ten months. If you were going to keep a group of people employed all year long, you needed some variety. That way if lumber wasn’t selling, then you could sell pots and pans. That’s how we hit upon the home-center concept.”

If there is one thing Egan has never been without, it’s ideas. “Every morning he wakes up with a new idea,” says Wayne Holmes, who has worked as his lawyer since the early 1970s. “A lot of them don’t pan out, but he never stops thinking.” Back in the 1950s, Egan built a modular show home on West Creek Road that caused quite a stir—especially since its asking price was an outrageous $12,000. He also worked hard to persuade the local banks to extend the term of their home mortgage loans from ten to fifteen years, even organizing a presentation on the topic that eventually resulted in his being named to the board of the Nantucket Savings Bank.

Egan’s efforts to “get things moving” were not always appreciated by his fellow Nantucketers, however. “At that time, anybody trying to do anything was an upstart,” he says. “If you got just a little above what was considered normal, there was great suspicion.”

On the other hand, Egan also remembers feeling a genuine sense of camaraderie among Nantucketers of his generation. “Youth relates to youth,” he says. “I used to help the contractors price out their jobs. It took a lot of pencil work, but it felt as if we were all working together.”

Contractor Richard Corkish, who was one of Marine Lumber’s biggest customers in the early days, claims that Egan’s success can be attributed to his ability to listen to and evaluate advice. Remembers Corkish, “He used to say, ‘I borrow other people’s brains.’”

One of the brains Egan often borrowed through the years was that of friend George Snell, a member of the Nantucket High School class of 1936 who made good in real estate in Washington, D. C. Even though he has been Egan’s regular golfing partner and occasional business partner (at one time the two of them owned the Inquirer and Mirror), Snell jokingly discounts his role as a mentor. “Sure, I’ve given Bud advice, but I don’t think he’s ever listened to any of it.”

Another person who has joined Egan in various ventures—from the purchase and sale (with three others) of the cranberry bogs, to serving on the airport commission—was the late Bob Congdon of Congdon & Coleman Insurance Agency. It was Congdon who first introduced Egan to the addictive pleasures of collecting art, an avocation that Egan now admits “has gotten out of hand.”

Egan also developed a unique relationship with woodcarver and ship model maker Nikita Carpenko, a Russian émigré who was a fixture on the Nantucket art scene in the 1950s and 1960s. The Marine Home Center shop gave him wood to make carvings that fetched a pretty penny at art galleries in New York. Egan also acted as Carpenko’s informal bank, placing the roll of cash that the artist would bring back from New York in the Marine Home Center safe.

When in the early 1960s Walter Beinecke became the managing partner of Lawrence Miller’s holdings, which had grown to include a wide range of businesses, Egan gained a front-row seat in the entity that would one day be known as Sherburne Associates. Beinecke says that he was immediately impressed with the man who ran the Marine Lumber Company: “Bud was the shining light of the local business personalities. He has an extraordinary amount of determination and a remarkably clear vision of Nantucket.”

In the winter of 1965 Beinecke was beginning to formulate a direction for the waterfront area. Although Sherburne Associates had hired an architectural consultant, Egan offered his own view of what Straight and Old South wharves might look like. “At the time I wanted to bring a whaleship to Nantucket in the worst way. It was my dream that you could see the bow of the whaleship from the steps of the Pacific Bank.” Working with the artist Doris Beer(“I talked, she sketched”), Egan produced a painting that Beinecke would later take to a Nantucket Rotary Club meeting to show what the wharves might one day look like. Pointing to a reproduction of the original painting, Egan says, “You can see the similarities between the sketch and what we have now.”

It was about this time that Beinecke made the decision to sell off many of the companies associated with Sherburne so that he could concentrate on the acquisition of real estate. After extensive negotiations, and with the help of some inheritance money from Dorothy, Egan purchased the Marine Home Center in 1965.

In 1972, tragedy struck Bud and Dorothy Egan when their only child Jane died at the age of twenty-six after a lifelong struggle with diabetes. Up until then Egan had found time to write a regular gossip column in the Inquirer and Mirror. But after Jane’s death, Egan says, “I just couldn’t put pen to paper anymore.”

While the success of the Marine Home Center might seem like a foregone conclusion today in the age of the “trophy house,” it was never easy, particularly in the years immediately following Egan’s purchase of the company. His willingness to take risks meant that he was always, in his own words, “spreading myself thin. The accountants would warn me that I was teetering on the edge. Luckily, the times bore me out.”

During the building boom of the 1980s, when it became difficult to secure enough truck reservations on the ferry, Marine Home Center purchased a giant transport plane, a C-19, capable of flying an entire flat-bed truck over from Hyannis. Although the plane experiment lasted only until 1987, it was typical of Egan’s willingness to try fresh ideas, no matter how risky they might seem. To this day, Egan maintains a large presence at the Hyannis airport, storing more lumber there than is ever on Nantucket at any one time.

In addition to a wide variety of business ventures, including the recent purchase of several buildings in the Nantucket Commons, Egan has been involved with more than his share of community organizations. From the Conservation Foundation, to the Boys & Girls Club, to the town’s publicity committee, to the Nantucket Historical Association (a thirty-five year stint), Egan has paid his dues. Through the formation of the Egan Foundation, he and Dorothy hope to positively impact the island’s cultural life for years and years to come.

Although his friends, and especially his wife, are constantly trying to persuade him to travel, Egan enjoys nothing more than a day at the office—along with, of course, a round of golf and a two-hour lunch with Dorothy at their ranch house on Mill Hill. Says his old friend George Snell, “Bud doesn’t need or want to go anywhere else. He’s a true Nantucketer.”

Nathaniel Philbrick is director of Egan Institute of Maritime Studies at the Coffin School and author of Away Off Shore.