Issues of Inclusion at the Museum and in Nantucket's Maritime History

By Charles J. “Chuck” Allard, Museum Manager

In February we reflect on the struggles and contributions of Black Americans to the history of the country, and it is important to look at how our Museum deals with issues of diversity and inclusion. Since we celebrate stories of bravery and self-sacrifice by the United States Coast Guard, its predecessor services, and volunteer organizations on Nantucket, can we identify parallels between our island’s history and these entities?

The present-day Coast Guard evolved from several different government organizations that over time were seen to share symbiotic skills and responsibilities. The merging of different operating cultures was the catalyst that created an organization willing to embrace change, focus on results and eschew outmoded traditions. Also, unlike other military services, the Coast Guard was relentlessly engaged in their mission during both war and peacetime.

From its beginning in the 1790s, the Coast Guard, originally established as the Revenue Cutter Service, welcomed minorities into its ranks on an equal basis. During wartime, the Revenue Cutter Service, and after 1915 the Coast Guard, operated as part of the U.S. Navy. From the War of 1812 into the 21st century white and black seamen fought America’s enemies side-by-side.

During and after the Civil War, the United States Lighthouse Service (part of the Coast Guard since 1939) appointed black freedmen and former slaves as Keepers, and as early as the 1880s, there were all African American staffs manning lighthouses. Around the same time, the United States Life-Saving Service hired African Americans as surfmen and station keepers, including the entire crew at the Pea Island Station, North Carolina, by 1896.

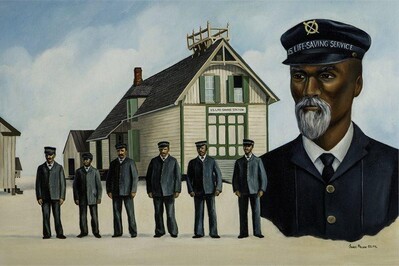

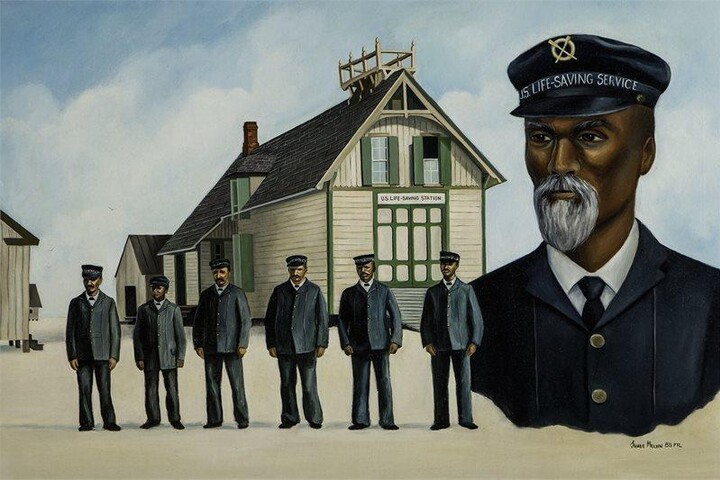

The First All Black Surfmen Crew, Pea Island

Reporter Stephanie Frederic, working with researchers and authors David Wright and David Zoby, tells the story of Keeper Richard Etheridge and the Pea Island Surfmen. In 1896 the crew performed an epic rescue in which they swam out to a wreck and saved all souls aboard when the conditions were too treacherous for a surfboat. Their heroic efforts were not acknowledged by the United States Lifesaving Service until 100 years later when gold medals were awarded, in their honor, and presented to their descended families.

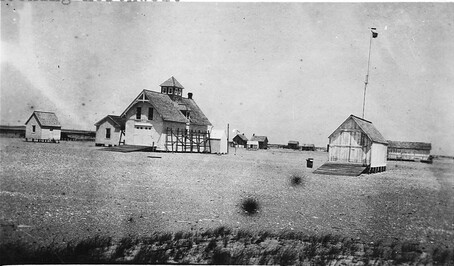

Photo credits: Richard Etheridge and the Pea Island Lifesavers painting by James Melvin, photo by NC Aquarium on Roanoke Island; U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Richard Etheridge dedication (the quarterboard was made from wood from his birthplace), photo by Petty Officer 2nd class Patrick Kelly; Historic images of the Pea Island lifesaving station and crew, images from the U.S. Coast Guard.

Nantucket's Community was Forward-thinking

The history of the island of Nantucket, with its legacy of worldwide whaling, out sized economic power, Quaker religious self-restraint, women's advancement and the suffrage movement, and support for abolition and school integration meant that the island's community was capable of forward-thinking on many social issues.

Nantucket merchants and whaleship owners manned their vessels with African Americans (both slaves and free men in the early years), native Americans, Azorians, Cape Verdians, Asians, and Pacific Islanders, and with some exceptions, they paid the same wages for the same jobs regardless of race, origin or creed. Many Nantucketers who later became surfmen or worked at lighthouses had once been on integrated ships.

It is doubtful that anyone rescued off a floundering ship cared about the ethnic background of the rescuer. But given the long history of Nantucket as a cosmopolitan port of business, why were there so few African American surfmen or lighthouse keepers serving on Nantucket? The answer is quite simple. Based on a review of federal census records from 1880 through 1930, the number of black residents, including women and children, in any of these census years, never exceed the 48 recorded in 1900. The federal census records for the years 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, indicate a total of 58 persons employed as surfmen, only one of whom identified as black (actually, mulatto), seven foreign-born, and nine born in a state other than Massachusetts. Throughout this period shapeshifting of racial identities was common. Therefore, the identification of a single black man may not be accurate, especially when one looks at how persons from the Cape Verde Islands were categorized, e.g., in 1910 they were described as white, in 1920 as Mulatto, and in 1930 as black. More confusing than edifying.