A Legacy of Infamy and Heroism

By Olivia Jackson

Torrents of rain. Unrelenting winds. Unforgiving swells. The evening of March 31 in 1879 was unforgettable. With little warning, a treacherous storm, to later be known as The Great Gale of 1879, battered and decimated countless ships and claimed the lives of many seamen over several days. In the storm’s wake it left a legacy of infamy and heroism that would forever be remembered on Nantucket.

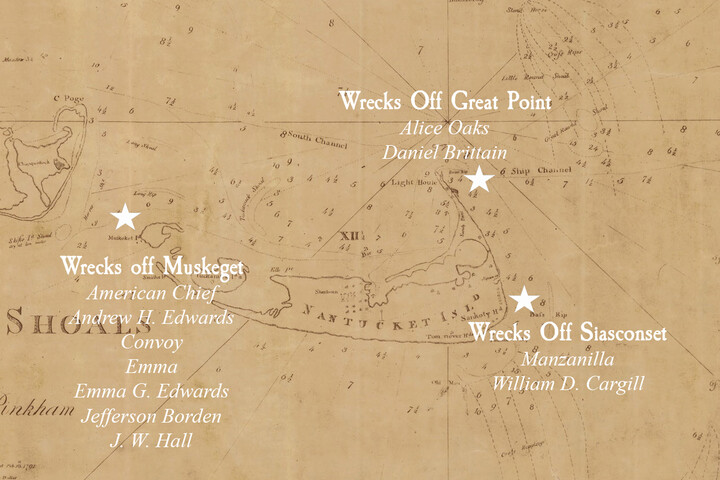

Nantucket was a recognizable landmark on busy trade routes along the coast in the 19th and 20th centuries. Many ships either passed north of the island or south of the island to reach popular ports such as New York and Boston. The shifting shoals off the island made it difficult to navigate the waters and the unpredictability of the weather added unforeseen challenges. Winters on Nantucket would often lead to a unique set of issues, including the harbor freezing, impenetrable ice, and potent, fierce forecasts, complete with wind, rain, snow, and fog. The winter of 1879 was no exception. The Great Gale of 1879 was by far the most disastrous and disruptive storm that season.

The Great Gale landed on Nantucket in the evening of March 31. As the night passed and morning came, the violence and ferocity of the storm increased. The wind grew in potency and force. The rain pounded the earth. The tide swelled and rose, nearly submerging the docks and the wharves. In an article in the Inquirer and Mirror published on Saturday, April 5, 1879, the storm was described, “’The sea grew white’ as if by magic, and as the elements raged more violently the thoughts of all reverted to the numerous vessels seen in the sound in the morning, it being evident to each one that shipwreck must inevitability follow such fury of the elements.” The destruction from the storm was immense, and although the exact number of shipwrecks from this ferocious gale was not confirmed, there are at least a dozen known wrecks.

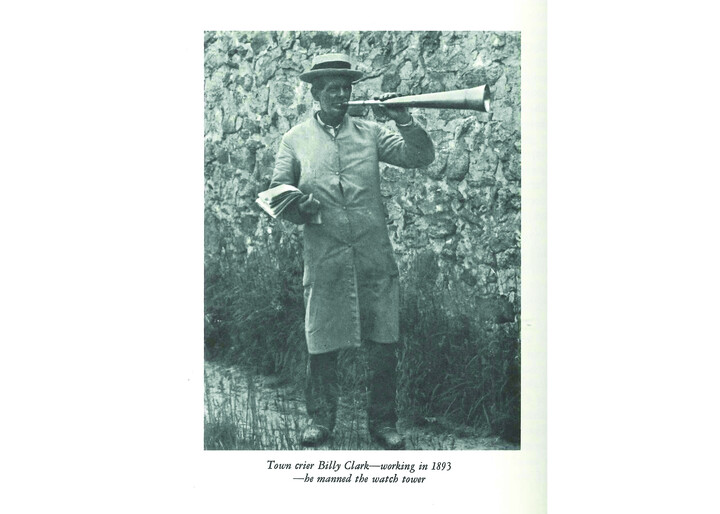

On the morning of April 2, “Billy” Clark, the Town Crier, informed Captain Thomas F. Sandsbury, the first Keeper of the Muskeget Lifesaving Station, that there were four vessels in distress off the west end of Nantucket. Sandsbury and a volunteer crew rowed a dory from Madaket to Tuckernuck, where they were able to access and launch the Massachusetts Humane Society’s surfboat; Captain Sandsbury and seven men then embarked on a rescue mission that would last 32 hours.

With four distressed vessels in sight, the first wreck that the crew rowed to was the schooner, J.W. Hall, bound for Lynn from New York with a cargo of 339 tons of coal. She had anchored in the sound to wait out the storm, but the force of the wind and waves broke her anchor chains; she wrecked near Muskeget. Allegedly, the rescue crew assisted four men off the schooner and into the surfboat, and according to several sources, brought the schooner’s crew to Tuckernuck before continuing with their mission. From there, Captain Sandsbury directed the crew to the schooner, Emma. She was bound for New Brunswick with a cargo of coal; she too had wrecked near Muskeget. However, upon arriving at the supposedly distressed schooner, it became apparent that the crew was in a less dangerous predicament than other vessels nearby. So the rescue crew rowed on.

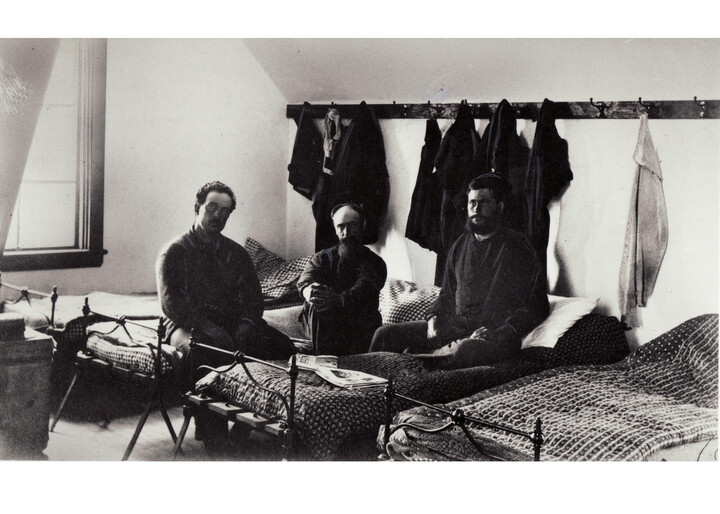

Captain Sandsbury and his seven men spotted a ship teetering in the crests of the seas in the distance. She appeared to be on her beam ends, meaning that the vessel was at an angle of 45 degrees or more to the surface of the water, practically capsized. For the rescue crew, the journey between Emma and this helpless schooner, the Emma G. Edwards, a distance of approximately four miles, was immensely challenging. Marcus Dunham, one of the seven men in the surfboat and the last of them to survive, recalled this particular row in later years for an article published in the Inquirer and Mirror on March 6, 1937. He said, “The seas kept breaking over us all the time we headed her into the wind. It was cold and the water was like ice. We couldn’t get anywhere near the schooner at first. She was lying on her side, her masts lifting to every sea and, as she had all sail set, every time she come down she’d sent the spray twenty feet into the air.”

The Muskeget crew during the winter of 1883, Judas Nickerson, Captain Thomas Sandsbury, and Marcus Dunham.

The Emma G. Edwards was a three-masted schooner headed for Boston from Philadelphia with a cargo of coal. She had anchored near Chatham on Monday morning, April 1, with hopes of waiting out the storm; however, the force of the wind and waves dragged the schooner through the sound all day until she struck Tuckernuck Shoal and rolled over on her beam ends. The schooner’s crew sought refuge in the topmast rigging, but the duration with which they were exposed to the unrelenting elements caused several men to fall into the ocean from exhaustion. On the morning of April 2, only two men were still alive. When Sandsbury and his crew arrived at the nearly capsized schooner, and were eventually able to position themselves with comfortable, safe proximity to the vessel—not any easy task—one man, Thomas Brown, was still clutching the rigging, feebly waving to the rescue crew. All but this man from the Emma G. Edwards’ crew perished.

As Dunham later recounted, “Finally, we got near enough to her for George Coffin to make a try getting aboard. George was a good swimmer and he volunteered to jump into the water and make his way to the men in the rigging.” Once on board, Coffin discovered that of the three visible men, two were dead. With a rope around his waist, Coffin retrieved the two deceased bodies, as well as assisted Brown to the surfboat. At this point, the waves and the surf prevented the rescue crew from returning to Tucknernuck; thus, instead, they rowed eleven miles back to town.

Upon arriving in town, Sandsbury and his crew brought the two bodies to the County Medical Examiner, Dr. J.B. King, who consigned the deceased to the Humane House on South Water Street, which served as a temporary morgue. Aware that the night ahead would be just as challenging and problematic as the previous 24 hours had been, Sandsbury and his rescue crew did not dither in town. They placed a whaleboat on a carrying rig, hauled it to Madaket, and launched as soon as possible. They made it successfully to Muskeget, where they spent the night, huddled under the boat for shelter, and waited for dawn.

The Muskeget Lifesaving Station circa 1885.

At daybreak, the crew set out again and rowed to two schooners that were fortunately not in need of assistance. They proceeded to Emma, assisted their crew into the boat, and returned to Tuckernuck, where they gathered the crew from the J.W. Hall. At 3 o’clock in the afternoon on April 3, 1879, the whaleboat, precariously loaded with human cargo, reached Madaket safely. The entire rescue mission lasted 32 hours, and was a true testament to the grit, determination, and bravery of Nantucket’s lifesavers.

Following the heroic efforts of Sandsbury and his crew, the Massachusetts Humane Society awarded Sandsbury a silver medal and twenty-five dollars, and each crew member was given twenty-five dollars. However, in an unprecedented move, the U.S. Treasury Department also issued silver medals to the crew and a gold medal to Captain Sandsbury. One of those medals, a two-sided medallion, awarded to Marcus Dunham, was donated to the Nantucket Shipwreck & Lifesaving Museum by Ingrid and Robbie Francis in 2009. The medal and a copy of the letter sent to Dunham from Secretary John Sherman of the Department of the Treasury in November 1879 are now on display and part of the Museum’s permanent collection.

Lifesaving medals on display at the Nantucket Shipwreck & Lifesaving Museum. The gold medal awarded to Captain Sandsbury is annually loaned to the Museum from the Nantucket Historical Association.

Author’s Note

The Great Gale of 1879 has an abundant amount of information. No two sources are alike in their recounting of the events, and thus, the details of this account are a compilation of gathered information in an attempt to share the most accurate version of this epic storm. Of the dozen shipwrecks, only three were discussed in depth in this article. If you would like to read more information about the Great Gale as well as the other vessels that were affected by this storm, Wrecks Around Nantucket by Arthur Gardner and/or Life Saving Nantucket by Edouard Stackpole are wonderful references for you to explore. Both provide details and accounts of this ferocious storm. To learn more about The Great Gale and lifesaving on Nantucket, be sure to visit Egan Maritime’s Nantucket Shipwreck & Lifesaving Museum, opening for the 2019 season on Saturday, May 25.