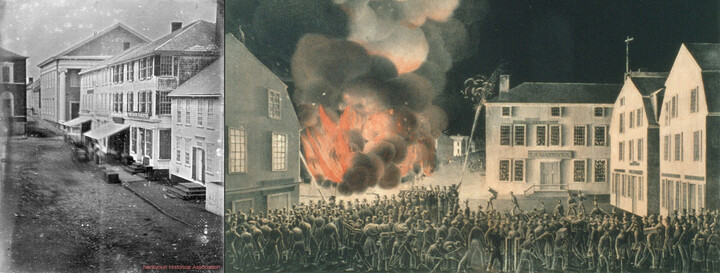

From the Egan Art Collection, Rodney Charman's "The Great Fire of 1846"

By Michelle Cartwright Soverino

On the evening of Monday, July 13, in 1846, William M. Geary closed his hat shop on Main Street (where the Lion’s Paw is located at the time of this writing) and walked home. Part of his closing ritual was extinguishing the daily fire he employed to warm his irons. On this particular evening, Geary had no reason to suspect anything was awry. Unbeknownst to him, there was a clogged stovepipe that would soon spark a flame.

The fire started around 11pm that evening. It was spotted by a watchman in South Tower on Orange Street. Though there were ten firefighting companies on the island, the efforts to extinguish and battle the flames were futile. Without a united force to work together under single leadership, differing opinions and debate kept the first responders from action. In the February 8, 1847 report submitted to the town by the appointed investigation committee, it reads,

“In contemplating the efforts which were put forth on this occasion to beat down the relentless enemy, your committee find some rare examples of devotion; worthy of all praise, amidst a host of instances, that deserve the deepest reprobation. Some of the engine companies maintained their posts manfully; others shrank away disgracefully from the field of action. In two instances the engines were utterly deserted, and were suffered to be consumed in the streets… These facts reflect a measure of dishonor upon us, such as has never before been either merited or hazarded.”

The Inquirer and Mirror, July 11, 1931, “1846—Eighty-fifth Anniversary of Nantucket’s ‘Great Fire.’”

The committee included William C. Starbuck, William R. Easton, and Job Coleman. They also commented that in addition to a weak response from the island’s firefighters, the densely populated narrow streets of Nantucket’s core downtown were populated with buildings and homes made of wood. There had been little rain in the days leading up to the fire—dwellings and businesses were dry to the bone. When paired with the wind that evening, it all created the perfection condition for the spark in William M. Geary’s hat shop stovepipe to quickly spread—town was a hot, dry, timber box.

“Explosions of gunpowder and torrents of water seemed alike unveiling, though directed by the stoutest arms and the most desperate and determined spirits. All night long were these doomed people thus exercised, harassed and foiled. Human strength and skill were at length exhausted, and the fire having engorged everything within its reach, subsided only for lack of other accessible materials.” (The Inquirer and Mirror, July 11, 1931, “1846—Eighty-fifth Anniversary of Nantucket’s ‘Great Fire.’”)

By 6am the next morning, Saturday, July 14, more than one third of the downtown business hub was reduced to rubble and ash. More than 200 families lost their homes, and some 400 buildings—all predating the Civil War—had been destroyed. In total, the fire consumed 36 acres of Nantucket’s densely populated, narrow streets town—the very heart of the island’s community and economy.

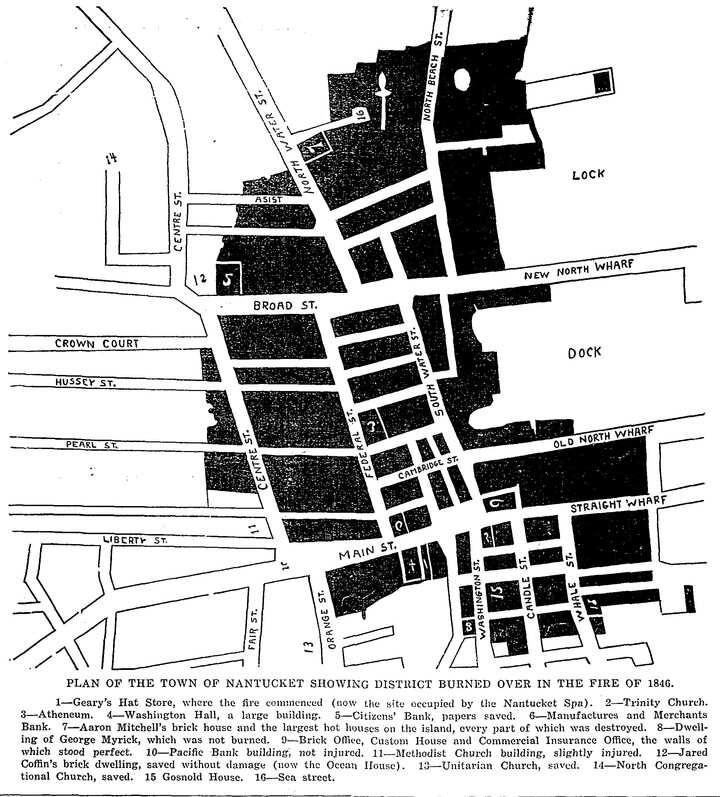

“It originated in the hat store of William M. Geary and, spreading up and down, burned all the buildings on the south side of Main Street, between Orange Street and Straight and South Wharves. Crossing Main Street it spread in all directions, consuming everything east of Centre Street between Main and Broad Streets, also the buildings on the west side of Centre Street… and Quince Street, fortunately sparing the Methodist church building. Crossing Broad Street it burned the fine Episcopal Church, and all buildings on the north side of North Water Street.” (The Inquirer and Mirror, July 11, 1931, “1846—Eighty-fifth Anniversary of Nantucket’s ‘Great Fire.’”)

Left: Main Street, 1845, before the Great Fire, with the Pacific Bank and the Methodist Church. Right: Lithograph by E.F. Starbuck with buildings engulfed in flames. Both images courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association.

Damage from the fire was estimated at $1-million, which in 2019 would be the rough sum of $31-million. Nantucket’s Selectmen sent an appeal to the mainland, knowing an effort to provide shelter, food, and clothing—beyond the funds needed to rebuild—was essential. They appealed:

One-third of our town is in ashes. A fire broke out on Monday evening last…and raged almost uncontrolled, for about nine hours. The whole business section of the town is consumed. There is scarcely a dry goods, a grocery, or provision store left standing….There is not food enough in town to keep wide-spread suffering from hunger at bay a single week….Hundreds of families are without a roof to cover them, a bed to lie upon, and very many of them even without a change of raiment. Widows and old men have been stripped of their all; they have no hopes for the future, except such as are founded upon the humanity of others.

We are in deep trouble….We need help–liberal and immediate…

“The amount of aid sent the stricken inhabitants from the mainland was large, contributions of money, clothing and provisions being sent at once from nearby towns. The city of Fall River loaded the steam 'Bradford Durfee' and sent her down to Nantucket as a relief ship a few days after the fire, and thousands of dollars were subscribed in Boston and other cities for relief of the Nantucketers.” (The Inquirer and Mirror, July 11, 1931, “1846—Eighty-fifth Anniversary of Nantucket’s ‘Great Fire.’”)

Rebuilding began almost immediately. The north side of Main Street was constructed with substantial brick buildings. The south side had temporary buildings put up that remained until 1926—a tribute to the lean years that followed the Fire due to the decline of whaling as well as the Gold Rush. The appointed investigation committee made sure lessons would be learned from the Great Fire. Though no life was lost, the island was devastated. In their February 8, 1846 report they shared, “In conclusion, your Committee would respectfully but earnestly call the attention of the Town, to the condition of what is called Gunter’s Alley, and to the instant and urgent necessity of converting that avenue, cost what it may, into a thorough fare, properly graded, and broad enough to allow the passage of engines, etc. between Union and Orange Streets.” Thanks to their efforts, Main Street was widened drastically, along with many of the Streets in Nantucket’s historic district.

The Great Fire of 1846, by Rodney Charman. Egan Maritime Collection.

In 1989, wanting to create a book with highlights of his commissioned collection of Charman paintings to share with the public, Bud Egan employed local Nantucket historian and friend, Robert F. “Bob” Mooney to write narratives for his selected works. The below paragraph was penned by Mooney for the project, which was published under Egan Maritime’s Mill Hill Press in its 1989 title, "Portrait of Nantucket, 1659-1890."

The Great Fire of 1846

The greatest catastrophe in the history of Nantucket was the Great Fire which erupted on July 13, 1846, destroying the entire business district of the town. Starting in a store on the south side of Main Street, the fire was whipped by an easterly wind which carried the sparks and flames to the nearby buildings and street. The meager water supply and fire-fighting equipment of the town proved inadequate to stem the tide of flames. Once the fire struck the oil-drenched waterfront, entire blocks erupted as the whale oil fed the flames at the wharves and warehouses. Four hundred buildings, including the heart of the island’s business community and the valuable museum of the Atheneum Library were demolished, but no lives were lost. Only the solid brick buildings of the Pacific Club and the Folger Block survived the disaster which reduced the downtown area to rubble. The next day, Selectmen sent a plea for help to the mainland, stating, “One third of town lies in ashes…” Aid and assistance were soon sent and the town responded with a burst of energy to restore the community with wider streets and more brick construction. The Atheneum was entirely rebuilt and reopened within six months. The Great Fire, however, was a crushing blow to the economy of the island, and was soon followed by the Gold Rush and the discovery of petroleum, events which foretold the end of the whaling era and the decline of Nantucket prosperity as a great port.