Walter Nelson Chase and His Award-winning Lifesaving Crew

By Olivia E. Jackson

When Captain Benjamin Pease retired from his post as the first keeper of the Coskata Life-Saving Station, he recommended Walter N. Chase, one of the first members of the Coskata crew in 1884, to be his successor. During his first year as keeper, Skipper Chase trained and practiced drills with his men every day, a tactic that worked to filter out the men who couldn't withstand and endure the practices. After one year, Chase and his crew were considered one of the best boat crews on the eastern seaboard, which would later be proven true in the great rescue of 1892.

Hovering at about twenty degrees above zero and with occasional snow squalls sweeping through, the night of January 20, 1892 began as a typical winter's night on Nantucket. Near midnight, a cold, forceful north wind picked up around Great Point, bringing with it driving snow and sleet. Despite the harsh weather and three of his men unable to work because they were sick, Skipper Chase ordered his crew out for their regular beach patrols. Among them, a young substitute named Roland Perkins, who had just reported back to duty from a lengthy battle with pneumonia.

Unbeknownst to the patrols, at this moment, the three-masted schooner H.P. Kirkham was battling her way through heavy seas and had become lost in the blinding sleet. The year-old schooner, manned by a crew of seven, was traveling from Halifax, loaded with salt and pickled fish, and was headed for the sanctuary of New York Harbor. Unable to keep the Kirkham on course and fighting a hopeless battle with the wind and sleet, the crew was desperately trying to avoid the dangerous shoals at the east end of the island; however, the most deadly of them, the Rose and Crown Shoal, lay directly in their path.

It was seven o’clock on the morning of January 21 when the Kirkham struck the dreaded Rose and Crown shoal, coming to a sudden, grinding halt 15 miles away from Great Point. The masts shuddered, and as the wind shredded the sails and the heavy seas rolled, seven terrified sailors strained at the ship’s railings to peer into the gale for some sight of land.

Fifteen miles from shore, at the farthest edge of hope, nearly beyond the limits of human endurance, a portion of the H.P. Kirkham’s bow was torn away and the big ship settled low on the shoal. With the decks awash, the crew fired red flares; however, fearing that their distress signals might never be seen, the men dragged an old feather mattress from their flooding quarters below deck, and with enormous effort managed to wrestle it high in the rigging where they ignited it.

Then they waited – to be rescued or to die.

However, when they ignited the mattress, which was remarkably still dry, it exploded with fury and the flash was seen by Sankaty Lighthouse Keeper, Joseph Remsen, who managed to confirm that he could see, through his spyglass, the Kirkham’s rigging. With the hand crank telephone newly installed by the Life-Saving Service, he called Skipper Chase at the Coskata Station and informed him of the situation.

“Before we put out,” Chase reported, “I’m calling for help from one of the Steamship tugs. I’m going to ask them to meet us at the shoal by nightfall. I know the wind and tide will be unfavorable for our return so we will sorely need a tow back to shore.”

At nine o'clock on the morning of the 21st, after carting the surfboat from the Chord of the Bay, or the inland side of the point, across the Great Point Strand, Skipper Chase and his crew launched from the east shore of the island. With a sail rigged for the following wind, Chase and his crew made it to Bass Rip in good time, but the Skipper’s earlier fears were realized when they spotted the Kirkham still roughly six miles away. It was too risky to head to her in a straight line, and thus improvising, Chase took a line moor from the Great Round Lightship to the schooner so that if the wind increased, he could always give up and take his men to the Lightship.

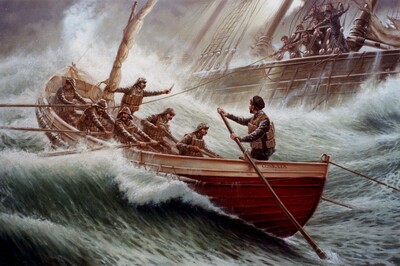

With the wind assisting their efforts, the Life-Saving crew approached the wreck. They could see the distant shapes of the men on the Kirkham clinging to her rigging. The hull of the schooner had almost settled under water, with only a bit of her railing showing on the windward side, which would ultimately be where Chase chose to make his approach. There would be no turning back now, not with lives at risk and the wind remaining favorable.

During the next hour, the training of Captain Chase and his crew would be tested. Not only did the Skipper, standing at his post in the stern, have to know how to maneuver his boat, but he had to be concerned with the racing tide, the surge of the waves against the wreck and the possibility of becoming entangled in the schooner’s rigging. There was no sign of the Steamship tug. They were alone, out of sight of land. One misstep and everyone would die.

Carefully, the Skipper eased his bounding rescue boat close. At twenty yards from her railing, he dropped anchor, signaling to his bowman, Jessie Eldridge, to toss the heaving stick and line to the stricken crew of the ship. As Chase watched, the desperate men of the schooner began to pull on the rescue line Eldridge had tossed them, drawing his surfboat dangerously close. One more wave and they’d smash against the wreck, the boat lost, the life-savers drowned. Skipper Chase, understanding the gravity of the situation, bellowed out to the seven freezing, anxious men aboard the schooner, "Stop hauling-stop, I say! Make your end fast. If you make one more pull on that line we'll cut it." To reinforce his point, he passed his knife to Eldridge, who stood up in the bow and held the knife aloft. The great figure of the life-saver’s commander, his billowing voice and the menacing knife had an instantaneous effect.

As a wave passed, Eldridge hauled on the line, pulling the rescue boat close enough to take one of the schooner’s crew members aboard. Once the man was in the surfboat, the line holding the rescue boat to the wreck was slackened off and the boat once again regained distance from the wreck. Wave by wave, the Coskata men crept close and then drifted away, taking one sailor at a time from the railing of the sinking ship. In minutes, all seven were aboard, wrapped in blankets and tucked beneath the seats as Chase pulled up the anchor, ordered that the sail and mast be cut away to lighten the boat, and began the difficult job of extracting his boat from the shoal.

The rescue boat now contained seven men from Coskata and seven frozen, half dead survivors from the Kirkham. The sandy bottom of the shoal could be seen at every wave trough. For three hours, while the crew laboriously worked to get out of the shoal, the Kirkham broke apart and eventually disappeared into the sea.

Six hours after the rescue, and ten hours since they launched the rescue boat from the shore, there was still no sign of the tug. The seas had grown far too rough for a larger vessel to come close. By now, the sun had set, the temperature had dropped to 18 degrees, and the wind and tide were against them. The rescue men were exhausted from the lengthy row and taxing effort that it took just to clear the boat of the shoal. They were too exhausted to battle against the tide and make it more than ten miles back to shore. Chase dropped the anchor. They were going to rest in the freezing cold while they waited for a change in the tide.

With every human instinct crying for shore and the shelter of home, Chase remained firm. Waves broke continuously over the boat. Snow squalls tore at the men. Chase let them rest no longer than ten minutes at a time to prevent them from freezing. Now and again, the beckoning flash of the Sankaty Lighthouse could be seen, but from nine o’clock that night until three o’clock the next morning, it seemed as though everyone had forgotten them.

Just when all seemed hopeless, the tides began to turn. Chase urged his crew to grab their oars and begin the challenging eleven mile journey back to shore.

On the morning of January 22, at nine o'clock, the Coskata crew was spotted from the Sconset bluff. The entire village was on the beach when they landed, helping the rescued men from the Kirkham and the heroic Life-Saving crew to warm, dry shelter. Chase was later told that his rescue boat, which he had ordered to be painted red so that it could be clearly seen, was recognized immediately from the bluff because of its distinctive color. The whole rescue mission had taken over twenty-four hours to complete.

Chase was taken to his uncle's house, where he later recalled, "My uncle gave me a cup of steaming coffee but I was shaking so much from the cold I had to go out-of-doors to drink it.”

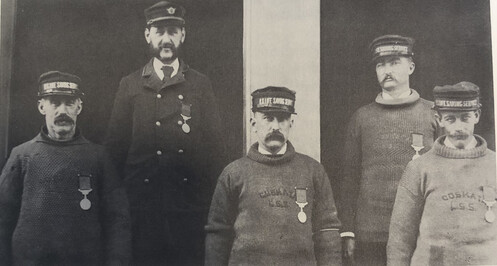

One year later, the Coskata Life-Saving men were awarded medals of Honor by the Congress of the United States. All but one of the crew attended. Roland Perkins, age 18, had fallen ill during the rescue and died just three months afterward.

At the presentation of the awards, Lieutenant John Dennett, U.S.N., presented the medals to Captain Chase and his men. Rev. Myron Dudley, pastor of the North Congregational Church, read the official commendation from Charles Foster, Secretary of the Treasury Department, which concluded with the following: "For more than twenty-four hours, day and night, you and your crew bravely battled with the winter storm. At every point you displayed superb seamanship, unerring judgment and dauntless courage. I am assured by sea-faring persons competent to judge of your great work that it was one of the most remarkable in the history of such achievements."

Details, Information, and Quotes taken from "Life Saving Nantucket" by Edouard A. Stackpole.