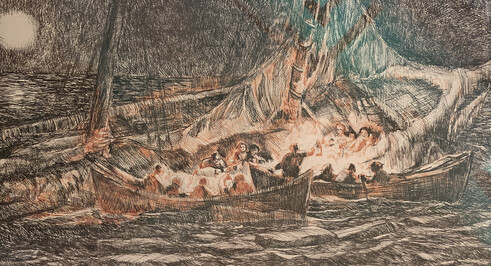

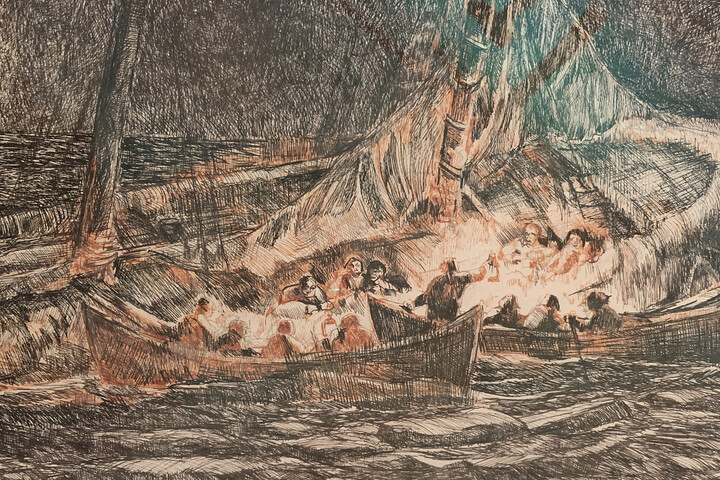

The Remarkable Rescue of the Crew Aboard the Shipwreck "Mary Anna"

By Michelle Cartwright Soverino, and Olivia E. Jackson

During the winter of 1871, Nantucket Sound experienced once of the worst freeze-ups in history; the ice was so thick that it was incredibly challenging and nearly impossible to cut through. At this time there was no paid lifesaving service on the island. Rather, volunteer surfmen with the Massachusetts Humane Society risked life and limb to aid mariners and passengers in distress on the shoals around Nantucket.

On the evening of February 3, 1871, the schooner, Mary Anna, with a cargo of coal destined for Maine, was anchored off the coast of Chatham when a cold, strong gale caused her to break from her mooring and begin to drift. There were five crew members on board. The ice on the boat and in the Sound affected their ability to maneuver and control the boat, and thus, on the morning of February 4, the Mary Anna struck a shoal and began to freeze in place. Ice slowly began to surround the hull and the crew fled to the rigging in fear that the vessel would be torn apart.

Their distress flag was spotted by patrols on shore. The steamer, Island Home, embarked on a challenging journey through thick, dense ice, but was unable to reach the stranded crew. In attempt to rescue the crew of the Mary Anna, the Island Home also became stuck in the frozen Sound and remained there for several days.

Meanwhile, on the Mary Anna, ocean spray had caused the ice to build up between two to three feet. The crew had abandoned the rigging, and had managed to build a small fire on the top deck. It provided little relief from the freezing temperatures, and they were forced to pace back and forth across the deck in order to say warm. By the time the surfmen reached the vessel, two of the five member crew had prepared themselves for death.

After several rescue attempts during the day, at about 10 p.m. on the night of the fourth, a crew of eight men in two dories ventured out to the icy shipwreck and her frozen crew. The volunteer surfmen found themselves in a difficult position: the ice was too thick for a surfboat, but not thick enough to allow people to walk across it. They were forced to go out with a combination of surboats and boards. When the surfboats failed, the surfmen would have to make their way slowly across the ice using the boards to distribute their weight to prevent the ice from breaking.

After two and a half hours they reached the ship, which was now on its side with just a part of her deck still out of the water. At roughly 3 a.m., the rescue surfmen and the five frozen seaman from the wreck made it back to shore. Had they endured a few more hours there is no doubt that several of the Mary Anna's crew would have died. The eight surfmen completed one of the bravest, most heroic rescues in Nantucket history and on one of the coldest, bitterest New England winter nights.

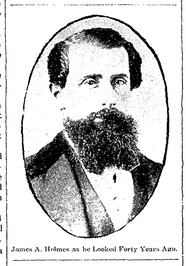

The surfmen were Isaac Hamblin, George A. Veeder, Alexander Janning, James A. Holmes, Joseph P. Gardner, William E. Bates, Stephen Keys, and Henry C. Coffin. All members of the rescue crew received a silver medal from the Massachusetts Humane Society, as well as thanks, praise, and some money raised by the town in recognition of their heroic volunteer efforts.

Pictured below is a photo of the medal awarded to James A. Holmes (on permanent display at the Nantucket Shipwreck & Lifesaving Museum); a photo of him from the The Inquirer & Mirror (Saturday, February 24, 1912 issue); along with a rendering (circa 2008) of the wreck of the Mary Anna detailing the fire aboard the decks in the final hours before rescue, done by Nantucket artist, David Lazarus; and a detail of Egan Maritime's painting, "Opening of the Nantucket Railroad," by Rodney Charman, featuring the Island Home on the wharf during a beautiful summer day.