As most readers know, there may be as many as 800 Nantucket shipwreck stories to tell. We want to pick a few that help us understand what happened, who were the rescuers that risked their lives for others, and what about sailors' luck.

What role does luck play in surviving a shipwreck? Being a sailor in the 19th century was a dangerous business, with about 30% never returning home and a career that did not last much beyond age 40. During the whaling era, men preferred to sign on a ship or with a captain known for "greasy luck," a reference to the dirty work of rendering whale oil from the animals' fat. Even today, sailors remain a most superstitious lot

Schooner Lucy Jones first wrecked on Nantucket Shoals on December 22, 1887. Was she a lucky ship or not?

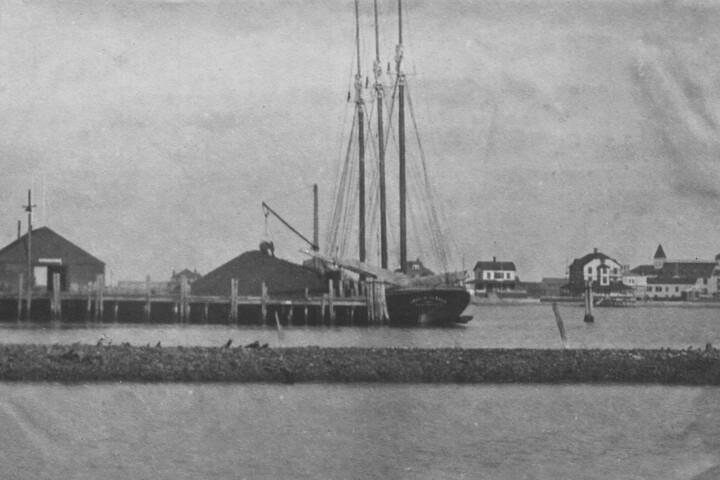

On a cold December 22nd morning, C. C. Crosby walked out of his Whale Street coal, grain, and feed warehouse into the growing storm, hoping to see the long overdue Lucy Jones. The schooner, heavily laden with a shipment of badly needed coal for delivery to Crosby, had stopped overnight at Vineyard Haven to take a pilot, Nantucketer William Burgess, aboard to get the ship safely through the treacherous Nantucket shoals.

When word came that a ship in severe distress was seen hard up on the bar near the entrance to the harbor, Nantucketers began to gather on Straight Wharf. While onboard the Lucy Jones, Captain Duncan, Burgess, and the 3-man crew risked freezing as they climbed into the rigging as waves crashed against the stranded ship and washed over the deck. Despite the increasing gale force winds, the insurance underwriter found he had more volunteer wreckers than needed, and 16 men who knew rescue was the first task were soon in the boat pulling oars on the way to try and save the crew.

From the shore and through the snow now falling, it was difficult to tell if the returning boat had saved the crew or was coming back without them. As the underwriters' boat approached Straight Wharf, the anxious crowd tried counting heads until someone yelled, "I see twenty-one. They have the crew and Burgess." Skill, perseverance, and a bit of old- fashioned luck were with them.

After the successful rescue and the crew safely on shore, additional wreckers gathered and, encouraged by the underwriter's promise of fifty percent of the value of all the coal retrieved, wasted no time launching boats and barges and heading for the wreck. Over the next few days, salvors piled it on Straight Wharf as coal was discharged from the vessel and brought ashore. Eventually, about three-quarters of the 240 tons were offloaded. According to Crosby, several tons disappeared at night and from the pile on the Wharf when the watchman was off duty. Records do not reveal any thieves were charged with this theft.

Nonetheless, it turns out that the cold winter of 1887/88 meant coal was in short supply on an island that spent half of January 1888 iced in. One coal dealer announced on January 20 that there was no coal for sale on the island.

With a reduced insured cargo in the hold, Captain Duncan and his crew could kedge the ship off the bar and get her alongside the Wharf. This action was a welcome outcome. Was Lucy Jones a lucky ship? It seemed so until the night of February 6, 1892, when off the Nantucket Shoals loaded with a cargo of brimstone (sulfur), she was rammed amidships by the steamer City of Savannah. The aged schooner broke apart, and of the five crew members, only two survived the collision. Luck is, after all, fleeting.

Several months after the 1887 rescue, the Massachusetts Humane Society rewarded the volunteers' selfless risks by presenting the princely sum of $96 to be divided by the 16 rescuers (listed below). All they had to do was apply to the Pacific Bank's cashier, A. G. Brock.

*Dedicated to the heroic fifteen [sic] who launched the life-boat, in a raging sea, and saved the lives of the crew of the Lucy Jones, stranded on Nantucket Bar, on the afternoon of December 22, 1887; The following are their names:

- Warren F. Ramsdell

- John M. Orpin

- Horace B. Cash

- Charles G. Coffin

- James M. Ramsdell

- Joseph P. Gardner

- James A. Holmes

- Arthur C. Manter

- William M. Barlett

- James Kiernan

- David H. Eldridge

- Leander Small

- George E. Orpin

- Samuel P. Winslow

- Edward W. Folger

- John P. Taber

The Inquirer and Mirror, Saturday, December 31, 1887, p. 2

*Don't hesitate to contact us if you find a family member on the list and have photos or stories you'd like to share

This Month in Maritime History is a new monthly series edited by the Museum’s Director, Chuck Allard, which draws inspiration from the island’s rich history of its relationship with the sea. To read past stories and learn more, click here