In 1846, Black Nantucket Mariner, Captain Absalom Boston, Took on the Town of Nantucket to Integrate the Island's Public Schools

By Michelle Cartwright Soverino

An element of seafaring history we at Egan Maritime find compelling is the freedom that men of all races, religions, and regions experienced aboard a Nantucket ship. From the island’s regaled whaling days to the early days of the U.S. Coast Guard, then known as the Revenue Cutter Service, minorities were welcomed on ships, though not always on an equal basis in rank. The crewmen were judged by the quality of their work, as was the division of wages. By sea, black Nantucketers were integrated into the crew. Some were even able to earn fortunes, and all lived freely on board the ships. As we focus on black history this month, and specifically black history in Maritime Nantucket, we must ask, did our black Nantucketers of days past receive equal treatment when they were off the ships and on the island?

The most celebrated black Nantucket mariner, Captain Absalom Boston (born 1785, died 1855), is known for being the island’s first whaling captain of color. To add to his notariety, in 1822 he was the first whaling captain to lead an all-black crew. Absalom was the son of an ex-slave and a Wampanoag. His mother's heritage rooted him deep into the island’s soil—far beyond his Quaker neighbors. Like many of Nantucket’s early sons, at the age of fifteen he left the island for his first whaling trip. Over several voyages he worked his way up the ranks. By the time he was thirty, Absalom was a retired whaling captain who was actively involved in multiple endeavors on the island and had a portfolio of properties.

Captain Absalom Boston (image via Wikimedia), to view the original painting you may visit the NHA Whaling Museum.

Absalom was, by today’s standards, a leader to be celebrated and admired. Though no longer working at sea, he was busy on land contributing to and providing for Nantucket's community; he operated an inn and a store. He was a founding trustee of Nantucket’s African Baptist Society as well as the African Meeting House, and became an active force in the island’s abolitionist movement. With so many roles in the community, it is hard to grasp why his daughter, Phebe, was denied acceptance to Nantucket’s public high school in 1846. It is especially hard to understand considering the state of Massachusetts had passed legislation in 1845 that all residents—regardless of color—were entitled to public education. Was Nantucket not a progressive Quaker community that provided equal ground for all its sons and daughters' education? Was equality, for Absalom and his fellow black Nantucketers, only truly experienced at sea?

African Meeting House, Nantucket, operated by the Museum of African American History.

It is clear that Nantucket circa 1850s was a land of selective and limited equality, and very separated. Yes, black and white islanders coexisted peacefully, but much of the island’s white community was publicly vocal about their desire to stay segregated. Phebe Boston was not the first young black Nantucketer to be denied entrance to the high school; in 1840, a stellar student, Eunice Ross, was also told she could not pursue a public high school education on the island. A few years later, in 1842, there was hope for equal education opportunities for all island youth when the public schools were desegregated for a day, but after much deliberation the island’s white community overturned the ruling.

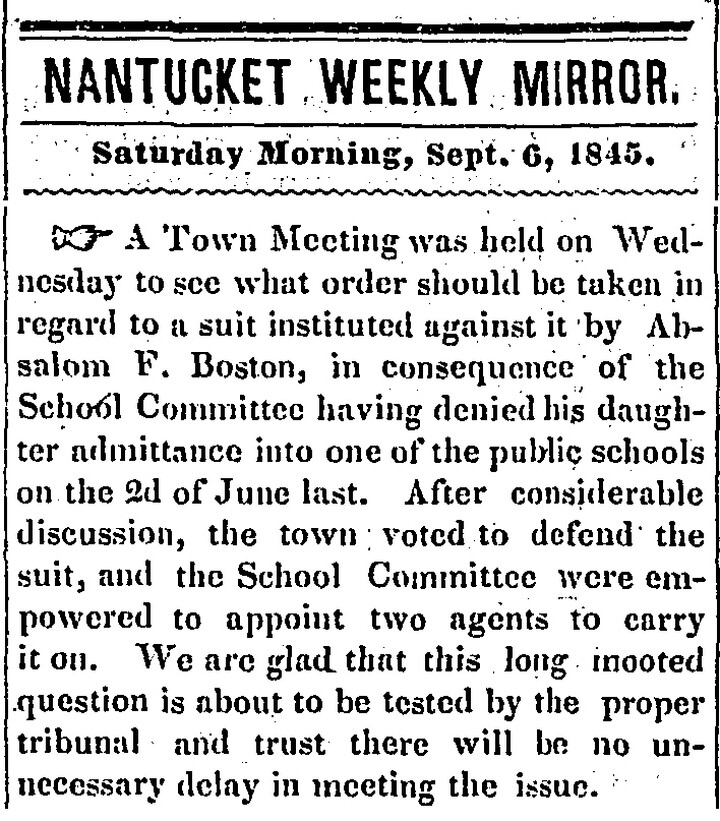

In 1846, Absalom was finally able to push the island to an integrated public school system after threatening the town of Nantucket with a law suit. The town, at first, seemed hopeful they would be able to win this case—as gathered from the Nantucket Weekly Mirror notice in 1845. But they soon realized with state legislation in Absalom’s favor, it would be prudent to allow Phebe—and Eunice—entry to Nantucket’s high school. And though it came with struggle, hardship, and resistance, it is remarkable to note that 100 years before Brown v. the Board of Education, schools on the small island of Nantucket were integrated.

This small story that carves Nantucket out as a progressive town ahead of its time also illuminates how incredibly embedded in the politics of race and segregation the island truly was. Equal but separate is far from an inclusive community, and though we don’t want to cast shade on Nantucket’s many contributions towards equality, history has a way of showing us lessons that still resonate, and the hardships that seem to inevitably follow accomplishments. Today, we recognize Absalom for not only his remarkable firsts as a black Nantucket whaling captain, but for pushing the advancement of non-white Nantucketers forward in a time of stark segregation. He made Nantucket better, giving us a progressive history to be championed.

Nantucket Weekly Mirror, 1845.